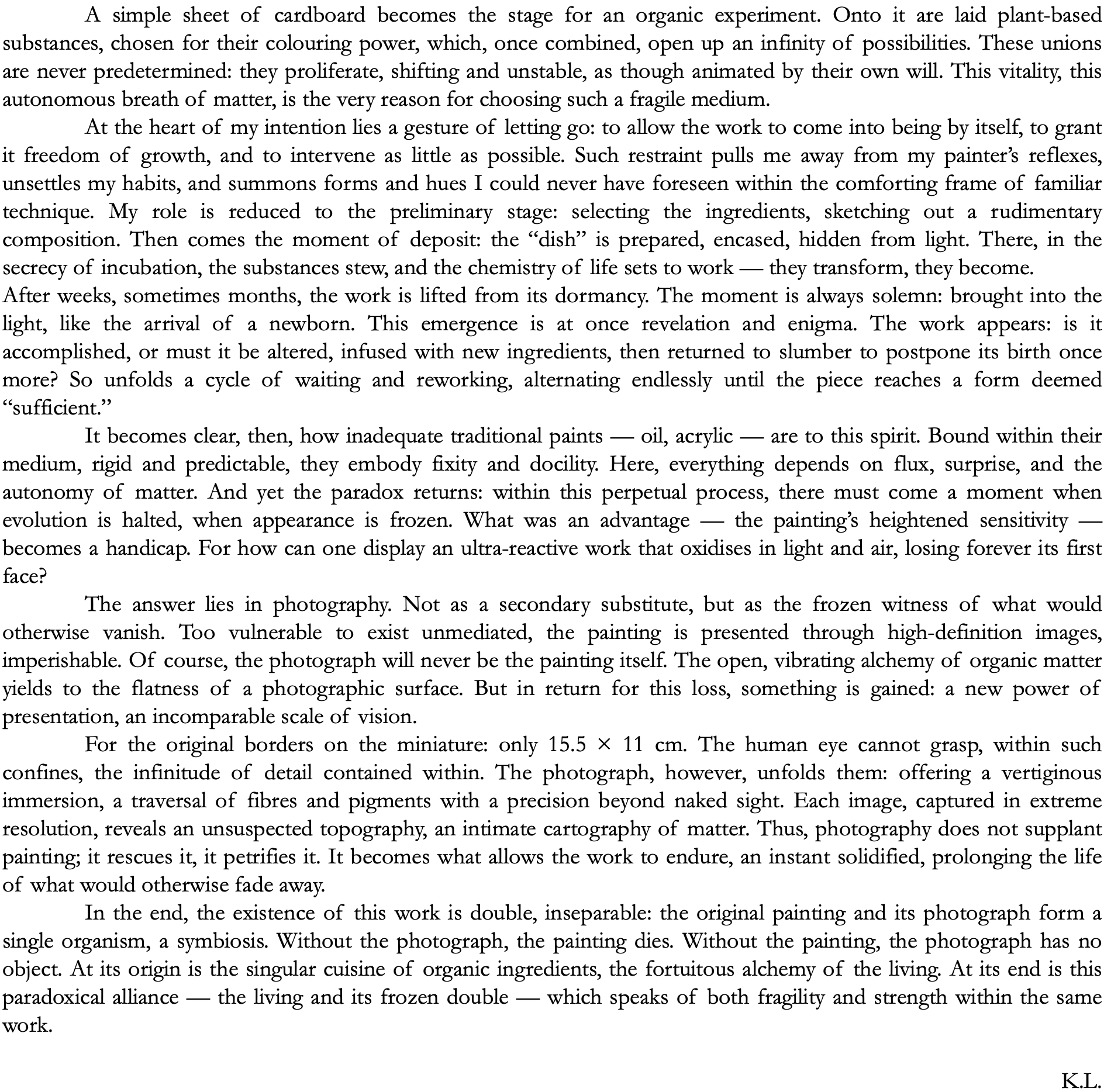

#242

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#241

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#240

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#239

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#238

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#237

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#236

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#235

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#234

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#233

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#232

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#231

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#230

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#229

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#228

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#227

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#226

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#225

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#224

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#223

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#222

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#221

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#220

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#219

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#218

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#217

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#216

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#206

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#205

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#204

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#203

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#202

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm

#201

Throughout the year 2025

Various plant materials: spirulina, beetroot, chlorella, turmeric, assorted matcha powders, spinach, lamb’s lettuce (mâche)

Charcoal; Liquid Ocean (Hydropassion); Micromix Drip (various micro-organisms) (Aptus); assorted moulds

15.5 × 11 × 0.3 cm